Free course on human rights

Free course on human rights

Human rights and law

introduction

This course examines the evolution of human rights and humanitarian law, subsequently delving into the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). The position of human rights in the United Kingdom and the impact of the Human Rights Act of 1998 will also be analyzed.

This OpenLearn course represents an example of level 1 study in Law.

At the end of this course, you should be able to:

- Understand the historical growth of the idea of human rights.

- Demonstrate an awareness of the international context of human rights.

- Demonstrate an awareness of the situation of human rights in the United Kingdom before 1998.

- Understand the importance of the Human Rights Act of 1998.

- Analyze and evaluate concepts and ideas.

The course will analyze the concept of law in its broadest sense:

The freedom to do something or to be protected from something. A claim to do or enjoy something. The power to do something that affects others and not to be challenged for that use of power.

This concept of rights defines the position of an individual and does not consider collective or majority rights. As you may already know, the subject of rights, and particularly human rights, is a growing area. There are several differing academic opinions, as ideas about rights change and expand alongside changes and developments in society.

Activity 1: Rights Time: 0 hours 15 minutes

The following table lists the articles and corresponding rights established by the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR). Look at that table and think of an example of a right for each of the three categories below:

The freedom to do something or to be protected from something. A claim to do or enjoy something. The power to do something that affects others and not to be challenged for that use of power.

Table 1: Articles of the European Convention and corresponding rights

| ECHR Article | Right |

|---|---|

| 2 | Right to life |

| 3 | Right to be free from torture and inhuman or degrading treatment |

| 4 | Freedom from slavery and forced labor |

| 5 | Right to liberty and security of person |

| 6 | Right to a fair trial |

| 7 | Freedom from retroactive penalty |

| 8 | Right to respect for private and family life, home, and correspondence |

| 9 | Freedom of thought, conscience, and religion |

| 10 | Freedom to receive and impart ideas and information |

| 11 | Freedom of association |

| 12 | Right to marry and to found a family |

| 13 | Right to an effective remedy |

| 14 | Right to enjoy the rights set forth in the Convention without discrimination |

| Protocol 1 Article 1* | Right to peaceful enjoyment of possessions |

| Protocol 1 Article 2 | Right to education |

| Protocol 1 Article 3 | Right to free and fair elections |

| Protocol 4 Article 1 | Prohibition of imprisonment for debt |

| Protocol 6 Article 1 | Abolition of the death penalty |

| Protocol 7 Article 2 | Right of appeal in criminal matters |

| Protocol 7 Article 3 | Right to compensation for wrongful conviction |

A total of 14 protocols have been added to the original ECHR. These reflect evolving cultures and needs.

2.1 Treaties, Conventions, and Constitutions

International human rights are part of a broader area of study, public international law, which generally encompasses the law relating to the legal rights, duties, and powers of a national state in relation to its dealings with other national states. These rights, duties, and powers are established in international treaties or conventions. Such treaties and conventions can be global in their application or limited to certain regions of the world. An analysis of international human rights treaties would reveal over fifty different treaties, conventions, and protocols (instruments that make changes to a treaty or convention).

Box 1: The Verdict on Public International Law

As this course (and other W100 courses available on OpenLearn: Europe and the Law, Judges and the Law, Making and Using Rules) examines rules, rights, and justice, it is appropriate to note for a moment that there are academic debates on the very existence of the concept of public international law. Individual national states are sovereign in the legislative process, and there is no international legislative body or court capable of enacting and enforcing binding laws for every national state in the world. This inevitably questions the status of international agreements and treaties, which are negotiated and agreed upon between national states. If there is no system to enforce or control such agreements, then what is the purpose of negotiating them? The answer to this question is that generally, there is a level of standard to which states adhere to gain acceptance within the world order. Any state that does not meet these standards risks incurring public condemnation from the United Nations or other nations whose acceptance and support (financial or political) that particular national state seeks.

At the end of the 17th century, major political, social, and economic upheavals saw the emergence of new democracies with written constitutions. Documents such as the American Declaration of Independence and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen began to lay the foundations for the recognition of rights such as freedom of speech and assembly. In these documents, one can see the development of modern international human rights law. Although these documents differed in their detailed content, they were supported by some general principles:

- Every human being has certain rights, which they possess by virtue of their humanity.

- No one can be deprived of these rights.

- The rule of law must be recognized. The rule of law requires that just laws be applied consistently, independently, impartially, and with due process. Laws are considered just when made in accordance with a fair and democratic procedure.

© United Nations Photo Library

Figure 1: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (the full text can be read on the United Nations website)

Such principles are often found in the written constitutions of national states. The media often use the American constitution as an example of a written constitution, but many other countries have similar constitutions, such as Australia, Canada, India, Italy, and South Africa. The United Kingdom has an unwritten constitution: in the UK, there is no single source of constitutional rights. It has been argued that this means there is greater flexibility and therefore greater protection of rights in the UK.

This is a topic we will return to later in this course when we examine the incorporation of the European Convention on Human Rights into UK law.

Each national state is considered sovereign, with complete freedom to deal with its citizens and territory. There may be a written constitution with rights for citizens or an unwritten constitution where rights are created through practice and custom. International law imposes constraints on national states. The development of international human rights law has been slow and incremental. Initially, national states entered into international pacts and agreements concerning trade and borders, matters that were in their personal interest and ensured stability and cooperation. The growth of international human rights law has been gradual and only emerged in the recognized forms today at the end of the 19th century. Since then, there has been enormous growth in the recognition of human rights. Today, there are numerous treaties and organizations for the protection of such rights. These include regional organizations: European, American, African, Asian, and Arab. Fundamental charters include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the European Convention on Human Rights, the American Convention on Human Rights, and the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights. In turn, there has been a growth in international courts and tribunals.

International Concerns on Human Rights: Slavery

Some of the earliest international concerns regarding human rights, as we recognize them today, were expressed regarding slavery in the late 18th century. The Somerset case of 1772 questioned the acceptance of slavery in the United Kingdom. This case is considered a turning point, as it was followed by the abolition of slavery in the UK. From this change in social, political, and legal attitudes towards slavery, a movement was born that sought to prohibit slavery internationally.

At that time, it was not possible to guarantee the freedom of slaves in all countries as different nations had different political and social attitudes. One of the first steps was to try to abolish the slave trade, with the aim of preventing a further increase in the number of slaves. In the following century, many countries abolished slavery. The League of Nations, established by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 to promote international peace and security and ensure the rights of minorities, proclaimed among its goals the complete suppression of slavery in all its forms and the slave trade by land and sea.

Slavery and all associated practices are condemned by Article 4 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 4 of the European Convention on Human Rights, Article 5 of the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, and Article 6 of the American Convention on Human Rights.

These rights have evolved over the past 250 years, and the prohibition against slavery is now well established in international law. The current challenge is not agreeing that slavery should be prohibited, but ensuring that such international norms are applied and respected.

Humanitarian Law: Growth and Development

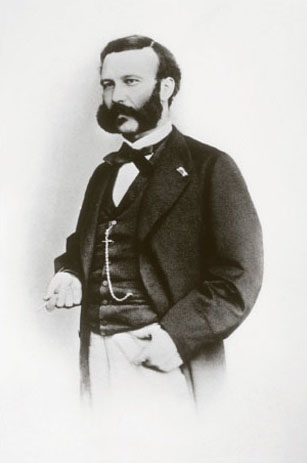

Humanitarian law represents another significant area in the growth of international recognition of human rights. In the 19th century, Henri Dunant, a Swiss philanthropist, observed the atrocities committed during numerous battles by the armies of national states. These experiences prompted him to create a permanent system of humanitarian aid, where private societies would complement the work of the military medical corps of national states.

In 1863, a conference of sixteen national states decided to adopt the emblem of a red cross on a white background (the reverse of the Swiss flag) as a symbol of humanitarian aid. The following year, in 1864, twelve national states signed the Geneva Convention, committing to:

- Respect the neutrality of military hospitals and their personnel.

- Care for sick and wounded soldiers, regardless of their nationality.

- Respect the emblem of the Red Cross.

This convention represented an important step towards international humanitarian protection, and its coverage has extended over time to include, for example, prisoners of war.

Recognition and Respect for Human Rights

The recognition of the conditions of the sick and wounded, along with the care of prisoners of war, has become a matter of interest in international law. This development has significantly contributed to the processes in which respect for the individual has become central and the respect for human rights a generally recognized international obligation.

The creation and expansion of humanitarian law have thus laid the foundations for a global system of protection and respect for human rights, establishing norms and principles that national states are required to uphold in situations of armed conflict and humanitarian emergencies.

Part A: Development of Humanitarian Law and Human Rights

Part A explored the development of humanitarian law and human rights. The progress of new democracies with written constitutions laid the foundation for the general recognition of rights such as freedom of speech. Some fundamental principles have emerged:

Intrinsic Human Rights

There are specific rights that a human being possesses simply by belonging to the human species. These rights are inalienable and do not depend on any external factor.

Inalienability of Rights

Such rights cannot be denied or taken away. They are inherent to the human being and must be respected and protected under all circumstances.

Rule of Law

The rule of law must be recognized and respected. This principle implies that just laws are applied consistently, independently, and impartially, with due process. Laws must be created and applied in accordance with a fair and democratic procedure.

These principles represent the foundation of modern international human rights law, which continues to evolve and strengthen through treaties, conventions, and the constant practice of humanitarian law.

Overview of the United Kingdom’s Perspective on Human Rights

In the United Kingdom, the issue of human rights has historically been addressed through the development of common law and the recognition of the supremacy of Parliament as the preeminent legislative body. Over the centuries, the lack of specific human rights legislation has posed an obstacle to the full development of such rights in England and Wales. However, the courts have sought to bridge this gap by developing common law to address issues related to individuals’ fundamental rights.

Historical Evolution

Supremacy of Parliament: By the late 17th century, the supremacy of the British Parliament was clearly established in the political and legal system. This meant that the courts considered themselves bound by Parliament’s legislation, preventing them from contravening clear and unequivocal laws.

Fundamental Rights: There was no written declaration of fundamental rights similar to those present in other written constitutions of countries like the United States. Individuals’ rights were generally limited only to the extent that Parliament had deliberately decided to do so.

Judicial Interventions: With the introduction of the Human Rights Act of 1998, the United Kingdom began to more formally integrate the principles of the European Convention on Human Rights into domestic law. This act allowed British courts to address cases where people’s rights were at stake, sometimes leading to decisions that contradicted the actions or laws of the government.

Legal and Social Implications

Landmark Cases: After 1998, numerous cases were brought against the British government, particularly against the Home Secretary, for violations of human rights guaranteed by the European Convention on Human Rights.

Role of the Courts: The courts have continued to play a crucial role in balancing individual rights with the interests of the state, often producing jurisprudence that has strengthened the protection of human rights in the United Kingdom.

Legislative Evolution: The introduction of regulations such as the Human Rights Act has influenced the interpretation and application of the law in the United Kingdom, highlighting a greater focus on human rights and their protection in the national legal context.

This historical and legislative framework provides a crucial background for understanding how the United Kingdom has addressed and continues to address human rights issues, integrating international norms and balancing national interests with international responsibilities.

Historical Evolution of Human Rights in Italy

Role of the Italian Constitution

The Constitution of the Italian Republic, which came into force on January 1, 1948, represents the main legal foundation for the protection of human rights in Italy. Born from the painful experience of World War II and the struggle against the fascist regime, the Italian Constitution is imbued with a strong commitment to the protection of citizens’ fundamental rights.

Key Articles: Part I, Title I of the Italian Constitution (Articles 13-28) enshrines a series of fundamental civil and political rights:

- Article 13: Guarantees the inviolability of personal liberty.

- Article 14: Ensures the inviolability of the home.

- Article 15: Protects the freedom and secrecy of correspondence and all other forms of communication.

- Article 21: Recognizes the right to freely express one’s thoughts through speech, writing, and any other means of dissemination.

- Article 24: Guarantees everyone the right to take legal action to protect their rights and legitimate interests.

Influence of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)

Italy ratified the European Convention on Human Rights in 1955, thereby committing to respect the human rights enshrined in the ECHR. This made the decisions of the European Court of Human Rights binding on Italy, and Italian courts are required to respect and apply the principles of the Convention in cases of human rights violations.

Recent Legal Developments

In recent decades, numerous significant cases have highlighted the importance of the ECHR in the Italian context. Italian courts, including the Constitutional Court, have often referred to the principles of the ECHR to resolve complex human rights issues.

Eluana Englaro Case: One of the most relevant cases concerns Eluana Englaro, a woman in a permanent vegetative state. The case raised issues related to the right to life and human dignity. The Court of Cassation eventually authorized the suspension of artificial feeding, based on the principles of self-determination and human dignity guaranteed by the Constitution and the ECHR.

Recently Adopted Human Rights Legislation

The Italian Parliament has adopted several laws to strengthen the protection of human rights:

- Law 67/2006: Measures for the judicial protection of people with disabilities who are victims of discrimination.

- Law 76/2016: Regulation of civil unions between same-sex couples and cohabitation arrangements.

Current Issues and Debates

Today, Italy continues to face significant challenges related to human rights, including immigration, the treatment of prisoners, and the rights of LGBTQ+ individuals. The judiciary, Parliament, and civil society play a crucial role in the debate and evolution of human rights protection in the country.

Conclusion

Italy has made significant strides in the protection of human rights through the Constitution, national legislation, and adherence to the ECHR. However, challenges remain, and ongoing dialogue among various social and institutional actors is essential to address these challenges and ensure the respect and protection of the rights of all individuals.

IMPACT OF THE ECHR ON ENGLISH LAW BEFORE THE HUMAN RIGHTS ACT OF 1998

Before the Human Rights Act of 1998, the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) had a significant but indirect influence on English law. The UK ratified the ECHR in 1951, and although it did not have direct effect in domestic courts, individuals could still bring cases to the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) in Strasbourg if they believed their rights under the Convention were violated.

Key Points:

Incorporation: Unlike in some other European countries, the ECHR was not initially directly incorporated into English law. This meant that domestic courts could not strike down legislation that conflicted with the Convention.

HRA 1998: Before the Human Rights Act (HRA) came into force, English courts had limited powers to consider human rights issues. If a domestic law conflicted with the ECHR, courts could issue a declaration of incompatibility, signaling to Parliament that the law needed amendment, but they could not change the law themselves.

ECtHR Jurisprudence: Despite the indirect nature of the ECHR’s influence, decisions from the ECtHR could influence English courts and lawmakers. Cases like R v. Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Brind (1991) demonstrated how ECtHR decisions could lead to changes in English law or government policy.

Political and Legal Pressure: The UK government and legal community faced pressure from Europe and domestically to align laws and practices with the ECHR standards, even before the HRA. This pressure often led to reforms or adjustments in policies to comply with human rights norms.

Impact on Public Discourse: The ECHR’s principles and decisions contributed to shaping public debates on human rights issues in the UK, fostering a growing awareness and discussion of rights protections.

In summary, before the Human Rights Act of 1998, while the ECHR did not have direct legal effect in English courts, its principles and decisions from the ECtHR influenced legal and policy developments in the UK, laying the groundwork for the more direct incorporation and enforcement of human rights under the HRA.

In Italy, the influence of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) on domestic legislation and case law has been significant, although the process of integration into domestic law followed a gradual and complex path.

Ratification and Reception of the ECHR in Italy

Italy signed and ratified the ECHR in 1955 through Law No. 848/1955. However, under Italian law, international treaties, including the ECHR, do not automatically become part of domestic law without specific implementing legislation. Therefore, despite ratification, the ECHR could not be directly applied by Italian courts until it was incorporated into national law.

Role of the Italian Constitution

The Italian Constitution of 1948 serves as the primary foundation for the protection of human rights in Italy. Articles 2 and 3 of the Constitution establish principles of equality and protection of inviolable human rights, providing a solid framework for integrating ECHR principles into domestic law.

Effects of the ECHR before Integration

Before the full integration of the ECHR into Italian domestic law, Italian courts nevertheless made use of the principles contained in the Convention:

Public Policy Sources: The ECHR and case law from the European Court of Human Rights were considered sources of public policy in Italy. This meant that courts could refer to ECHR principles to address complex human rights issues, even though they were not legally bound to do so.

Interpretation of Laws: In dealing with ambiguous interpretations of national laws, Italian courts used the ECHR and Strasbourg Court case law as interpretative tools to ensure greater consistency with human rights.

Development of Common Law: Where specific legislative provisions were lacking, courts integrated ECHR principles to develop common law, thereby filling regulatory gaps and strengthening the protection of fundamental rights.

Influence of the ECHR on Italian Case Law

With the formal integration of the ECHR into Italian domestic law through ratification and subsequent implementing laws, courts gained the ability to directly apply the rights established by the Convention. This led to greater legal coherence and certainty in decisions regarding human rights in Italy.

Role of the Constitutional Court

The Italian Constitutional Court played a key role in interpreting the Constitution to harmonize it with the ECHR. Through various rulings, the Court recognized the importance of the ECHR as a tool for human rights protection and promoted constructive dialogue with the European Court of Human Rights.

Conclusion

The integration of the ECHR into Italian law represented a significant step forward in protecting human rights in the country. Despite initial limitations in its direct application, Convention principles played a crucial role in enhancing the legal protection of fundamental rights in Italy. The Italian Constitution and the Constitutional Court played a decisive role in ensuring that ECHR principles were fully integrated into the national legal framework.

3.5

The European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR) has had a significant impact both in the United Kingdom with the Human Rights Act (HRA) and in Italy through the process of integration into domestic law via ratification and subsequent implementing legislation.

In the United Kingdom, the historical approach of Common Law viewed human rights as deriving from legal tradition and court decisions, with the supremacy of Parliament limiting the direct application of international treaties like the ECHR until the introduction of the HRA. After the HRA came into force in 2000, the ECHR was more formally integrated into British law, allowing courts to directly apply the rights established by the Convention.

In Italy, the situation was influenced by the tradition of Civil Law, where international treaties such as the ECHR must be incorporated into domestic law through ratification legislation to become effective. Despite ratification in 1955, the full application of the ECHR occurred gradually, with Italian courts initially referring to Convention principles as a source of public policy and interpretative tool before complete integration into national law.

In both cases, the influence of the ECHR has promoted greater protection of human rights, enhancing the coherence and effectiveness of national jurisprudence in alignment with international human rights principles.

Part 2 Insights on law enforcement

We have seen a detailed description of the legal requirements of necessity and proportionality that must be met for the use of force by law enforcement to be lawful under international human rights law. Here is a summary of the fundamental principles:

Legality: Police use of force must be based on clear and precise rules established by national legislation and must serve legitimate purposes such as law enforcement, arrest, or the protection of oneself or others. It is not lawful to use force for illegal purposes such as punishment or intimidation.

Necessity: The use of force must be necessary to achieve a legitimate objective. Law enforcement officers must exhaust non-violent means before resorting to force. The amount of force used must be the minimum necessary to achieve the desired objective and must be proportionate to the seriousness of the situation.

Proportionality: The use of force must be proportionate to the threat presented. This means that the harm caused by the use of force should not exceed the harm that is being prevented or controlled. Law enforcement officers must use the least harmful and effective level of force in the specific circumstances.

These principles are essential to ensure that the use of force by law enforcement respects the fundamental human rights of those involved. Proper application of these principles helps to reduce the risk of abuses and ensures that law enforcement acts responsibly and legally in their duties of maintaining public order.

The police have the duty not to discriminate against people in any way. Prohibited grounds include race, national or ethnic origin, indigenous identity, social or economic status (including property), color, birth, descent, occupation, religion, social origin, language, political or other opinion, age, sex, sexual characteristics, sexual orientation, gender, gender identity, gender expression, marital and family status, genetic characteristics, disability or other status. Discrimination is not only harmful but also perpetuates inequality.

This duty also applies to the decision and circumstances in which the use of force is resorted to. The use of force must be guided solely by the principles of legality, necessity, and proportionality, as explained in Lesson 2. However, the discriminatory use of the police power to use force is a widespread phenomenon around the world, involving the excessive or illegal use of force based on racist or discriminatory motives or attitudes, or as a result of unconscious bias. Often, this affects marginalized or minority communities.

Indigenous Peoples and Discrimination

Indigenous peoples frequently report discrimination by the police, such as frequent and unnecessary questioning, excessive use of force, the use of laws to arrest those who protest, violence against women, forced evictions, and torture or other ill-treatment. There are 476 million indigenous people worldwide, spread across more than 90 countries.

Indigenous peoples constitute about 5% of the world’s population, with the majority, 70%, living in Asia. They face the same harsh realities: eviction from their ancestral lands, denial of opportunities to express their culture, physical assaults, and treatment as second-class citizens.

Control of Refugees and Migrants at the Borders between Belarus/Poland and Lithuania/Poland since 2021

In Latvia, Lithuania, and Poland, the police have violently pushed back refugees and migrants, mostly from the Middle East and sub-Saharan Africa, at the countries’ borders with Belarus. Many have been subjected to human rights violations, including secret detention and even torture.

In August 2021, Latvia introduced a state of emergency following an increase in the number of people encouraged to travel to the border by Belarus. Contrary to international and EU law, and the principle of non-refoulement, the emergency rules suspended the right to seek asylum in four border areas, allowing Latvian authorities to forcibly and summarily return people to Belarus.

The disparate treatment given to migrants and refugees from Belarus, especially when compared to the attitude shown towards the much larger number of people fleeing Ukraine, strongly suggests a fundamentally racist and discriminatory approach.

Below are some examples of regional human rights standards regarding the use of force. Take a moment to explore the region that interests you.

AFRICA

The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights has issued specific guidelines on law enforcement’s control of assemblies in Africa:

21.1.2. The use of force must be an exceptional measure. Law enforcement officials must apply non-violent methods before considering the use of force and firearms. These means can only be used if other methods to achieve legitimate law enforcement objectives are ineffective or unlikely.

21.1.3. When the use of force is unavoidable, law enforcement must minimize harm and injury, preserve human life, and provide immediate assistance to injured persons, informing their next of kin.

21.2.1. Assembly operations must be planned with tactical measures to avoid the use of force. If the use of force is necessary, it must be proportionate, and commanding officers must ensure that all precautions have been taken.

EUROPE

The European Code of Police Ethics emphasizes:

The police may use force only when strictly necessary for legitimate objectives.

It is the duty of the police to verify the legality of the actions they intend to undertake.

AMERICAS

The principles on persons deprived of liberty in the Americas state:

Principle XXIII, 2. The staff of detention centers must not use force or coercive means except in exceptional, serious, urgent, and necessary cases, as a last resort to ensure safety and internal order, protecting the fundamental rights of detainees, staff, and visitors.

These standards reflect the commitment of the African, European, and American regions to limit the use of force by law enforcement to necessary and proportionate situations, while ensuring the respect of fundamental human rights.

The Declaration on Human Rights of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), adopted by the ten ASEAN member states in 2012, is not cited in this course because Amnesty International considers it incompatible with international human rights law and standards. In particular, its overarching “General Principles” grant broad powers to governments to violate rights.

The police may resort to the use of lethal force only in entirely exceptional circumstances.

Principle No. 9 of the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials clearly outlines the circumstances under which the use of firearms by police officers is justified. Here is a summary of its guidelines:

Self-defense: Officers may use firearms to defend themselves or others against an imminent threat of death or serious injury.

Prevention of serious crimes: Firearms can be used to prevent the commission of a particularly serious crime that poses a serious threat to life.

Arrest of dangerous individuals: It is permissible to use firearms to arrest a person posing an immediate threat and resisting authority, only when less extreme means are insufficient to achieve this objective.

Prevention of escape: Firearms may be used to prevent the escape of a person only if there is a serious risk that they may seriously endanger the lives of others.

In all cases, the intentional use of firearms must be strictly unavoidable to protect life. These principles reflect the international regulatory approach aimed at limiting the use of firearms by law enforcement to exceptional and strictly necessary circumstances, in accordance with the principles of proportionality and necessity.

The police must protect life, including those they are attempting to stop or arrest. Firearms are designed to kill, and any use of a firearm is considered potentially lethal. Even a shot aimed at the legs can cause death due to severe blood loss if it hits a major blood vessel. Therefore, based on the principles of necessity and proportionality, law enforcement officers are allowed to use lethal force only in entirely exceptional circumstances:

- It is justified to risk someone’s life only if it serves to save another life (principle of proportionality).

- It must be the last resort, with no other less damaging and likely effective means available (principle of necessity).

A firearm is a weapon designed to take a life. A rifle or handgun is almost always considered a firearm, as their standard ammunition load is designed to be lethal. A hunting rifle can be a firearm if loaded with ball or other lethal ammunition but may not be if loaded with tear gas, pepper spray, or other less lethal rounds.

The threshold for the use of firearms is governed by international standards, particularly the United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, and directly applies the principles of necessity and proportionality.

Law enforcement officers should not use firearms against individuals unless it is in self-defense or defense of others against imminent threat of death or serious injury, to prevent the perpetration of a particularly serious crime posing a grave threat to life, to arrest a person presenting such danger who resists authority, or to prevent their escape, and only when less extreme means are insufficient to achieve these objectives. In any case, intentional lethal use of firearms can only be justified when strictly unavoidable to protect life.

United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, Principle No. 9

The Basic Principles do not define “serious injuries,” but generally refer to injuries that endanger life or alter it significantly, such as loss of limb or loss of organ function. In many cases, a police officer cannot know or assess at that precise moment whether a threat, such as an attack, could cause serious injury or death. Serious injuries should therefore be considered a threat of seriousness comparable to a threat to life. It is essential that national legislation clearly states that only a threat of death or serious injury, and not any other threat below this threshold, justifies the use of a firearm.

However, the risk of a lethal outcome does not mean that the person’s death should be assumed from the outset. It should be considered an undesirable outcome, and law enforcement officers must take every precaution to prevent loss of life.

Law enforcement officers must not use firearms against individuals except to prevent the perpetration of a particularly serious crime that poses a serious threat to life, to arrest a person who presents such danger and opposes their authority, or to prevent their escape, and only when less extreme means are insufficient to achieve these objectives.

United Nations Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, Principle No. 9

When police intervene to prevent a crime, the use of firearms can only be justified to prevent a crime that poses a serious threat to life. It would not be proportional to use a firearm to prevent other types of crime, such as property crimes or even crimes that endanger people physically, unless it can reasonably be concluded that the suspect, if allowed to escape, would pose a threat to another person’s life. In practice, this can apply only in a minimal number of cases, such as a serial killer who, if allowed to escape, would reasonably continue to kill other people (of course, only if there are no other less damaging means available to prevent escape). In other circumstances, if they cannot prevent it without using lethal force, the police should let the suspect escape.

The principle of “protection of life” requires that lethal force cannot be intentionally used solely to protect law and order or to serve other similar interests (e.g., it cannot be used solely to disperse protests, arrest a suspected criminal, or safeguard other interests such as property). The primary goal must be to save lives. In practice, this means that only the protection of life can satisfy the proportionality requirement where lethal force is intentionally used, and protection of life can be the only legitimate objective for the use of such force. A fleeing thief who poses no immediate danger cannot be killed, even if it means the thief will escape.

Report of the United Nations Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, A/HRC/26/36, para. 72

While any use of a firearm carries a significant risk of causing death, intentional lethal use of a firearm refers to using a firearm in a way that will definitively cause the immediate death of the person, with no chance of survival. For example, a “sharpshooter” aiming at a person’s head or a police officer firing multiple shots into the central body mass of a person until they stop moving.

Such use of firearms can be authorized only in the most extreme situation of life-threatening danger, where only the death of the dangerous person can prevent loss of life for another person who is imminently threatened. In any case, the person’s death must always be a means to an end (preventing loss of another life) and never an end in itself.

Extrajudicial executions are deliberate and illegal killings carried out on the orders of a government or with its complicity or acquiescence, or by a state official or agent acting without orders. Extrajudicial executions can be carried out by regular military or police forces, by special units created to operate without normal supervision, or by civilian agents working with government forces or with their complicity. Extrajudicial executions are sometimes carried out beyond international borders.

If intent to kill cannot be established, homicide may still be unlawful.

When can law enforcement officers legally use firearms?

Police officers have a duty to protect life, including that of individuals they are attempting to stop or arrest. Firearms are designed to be lethal, and any use of a firearm is considered potentially deadly. According to the principles of necessity and proportionality, officers are allowed to use lethal force only in extremely exceptional circumstances:

Self-defense or defense of others against imminent threat of death or serious injury:

- Firearms can be used only when less extreme measures are inadequate to achieve these objectives.

- It is justified to risk someone’s life only if it is to save another life (principle of proportionality).

UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, Principle No. 9

Prevention of a particularly serious crime that poses a grave threat to life:

- Officers can use firearms to prevent the commission of a particularly serious crime only if there is a serious threat to life.

- It would not be proportional to use a firearm to prevent other types of crime, such as property crimes or even crimes posing physical danger to people, unless it can be reasonably concluded that the suspect, if allowed to escape, would pose a threat to another person’s life.

Report of the UN Special Rapporteur on Extrajudicial, Summary or Arbitrary Executions, A/HRC/26/36, para. 72

Arrest of a person who poses such a danger and resists their authority or to prevent their escape:

- The use of firearms is permitted only when less extreme measures are insufficient to achieve these objectives.

- The primary objective must be to save lives.

UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, Principle No. 9

Duty to issue a warning

Law enforcement officers must issue a verbal or visual warning, clearly expressing the principle of necessity:

- Identify themselves as law enforcement officers.

- Clearly warn of their intention to use firearms.

- Allow sufficient time to respond to the warning.

Officers must follow this procedure unless it poses a risk of death or serious harm to others, or is inappropriate or useless in the circumstances of the incident.

UN Basic Principles on the Use of Force and Firearms by Law Enforcement Officials, Principle No. 10

Warning shots

Some police forces consider warning shots as a means to warn of the imminent use of a firearm. Firing warning shots is inherently risky and should either be prohibited or considered only as an exceptional means of warning. A warning shot already constitutes the use of a firearm, and a warning is required before the shot is fired.

Protection of Third Parties

Police may only use lethal force against the person who poses a threat to life or serious injury. It is not justifiable to intentionally or knowingly put the lives of third parties, such as bystanders, at risk, even if the use of lethal force against a specific individual would be necessary and proportionate. Protecting third parties must take top priority.

Planning and Precaution

When planning and executing an operation, police must consider the lives of third parties, the suspect, and their own lives. Operations should be prepared and conducted in a manner that minimizes the risk of life-threatening situations. Decisions on when, where, and how to intervene should take into account potential risks inherent in the operation. When risks appear too severe, police should consider alternative options, such as a different time or location, or only proceed when sufficient backup and protection devices are available.

The protection of third parties should dictate how police plan and execute a law enforcement operation. If an operation poses a high risk to third parties or could result in their death, police must find a safer alternative.

🔎 Example: If police are planning to arrest an individual and expect strong resistance because the suspect is armed, the arrest should be scheduled at a time or place with fewer risks to other people. This could mean in the evening at the person’s home rather than during the day on a busy street with many people around.

Automatic Firearms Have No Place in Routine Law Enforcement Duties

Automatic firearms, which fire multiple bullets in rapid succession with a single pull of the trigger, are not suitable for routine law enforcement tasks. These weapons are inaccurate and do not allow for precise aiming, endangering the lives of bystanders and complicating the individual accountability of officers for each shot fired.

Protection of Bystanders

The use of automatic firearms significantly increases the risk of hitting uninvolved persons. Firing multiple bullets in rapid succession is less accurate than a single shot, and “stray bullets” can directly or indirectly hit bystanders by ricocheting off surfaces. This risk is unacceptable for the daily operations of law enforcement, which must prioritize public safety.

Accountability for Each Shot

Every shot fired must be justified as necessary and proportionate. Once the threat has been neutralized with the first shot, additional shots become disproportionate and constitute excessive use of force. Automatic fire does not allow police to continuously reassess the situation and the need to keep shooting, compromising their ability to keep the use of force within legal limits.

Automatic Weapons Are Unsuitable for Daily Police Activities

In extreme circumstances, such as during operations where multiple exchanges of gunfire are likely, the use of automatic firearms may be justified. However, this is an exception. For daily activities, automatic weapons are inappropriate. Law enforcement officers carrying firearms with both single-shot and automatic modes must keep these weapons permanently in single-shot mode, switching to automatic only in extreme situations and according to clear instructions on when it is appropriate.

The unjustified and therefore illegal use of firearms by police is often linked to discriminatory practices targeting certain groups or individuals, particularly those from marginalized or minority communities. This type of discrimination can manifest in various ways, but it is especially evident through the excessive surveillance of specific regions and the disproportionate targeting of people based on race, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, gender, or neighborhood of residence. Such discrimination not only unfairly associates these individuals with criminal activities but also subjects them to large-scale police operations characterized by high levels of violence, further perpetuating systemic biases and distortions.

Examples of Discrimination in the Use of Force

A notable example of this issue is the excessive and discriminatory surveillance of certain regions. In these situations, law enforcement officers often resort to the illegal use of lethal force, disproportionately impacting the residents of these areas. This phenomenon is fueled by systemic biases and further perpetuates such discrimination.

Data and Analysis from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights

The June 2021 report by the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, titled “Promotion and Protection of the Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of Africans and People of African Descent Against Excessive Use of Force and Other Human Rights Violations by Law Enforcement Officers,” analyzed 190 incidents where police killed Africans and people of African descent. Of these, 98% were reported in Europe, Latin America, and North America. Most victims were men from poor communities and men with psychosocial disabilities. About 16% of the victims were women, 11% were children, and 4% were LGBTI individuals.

Contexts in Which Police Killings Occur

The analysis revealed that 85% of police killings occurred in three main contexts:

- Enforcement of minor traffic violations, traffic stops, and stop-and-frisk: Police often use lethal force in situations that do not warrant such a level of violence.

- Police interventions as first responders in mental health crises: Instead of providing appropriate assistance, police frequently resort to lethal force.

- Special police operations: During these operations, lethal force is used disproportionately, often affecting the most vulnerable individuals.

Conclusion

The unjustified use of firearms by police is closely linked to systemic discriminatory practices targeting specific vulnerable groups. This behavior not only violates human rights but also perpetuates cycles of violence and discrimination that must be addressed through systemic reforms and strict accountability for law enforcement.

Regional Standards on Human Rights Regarding Discrimination and Use of Force

Africa

African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights – Article 4

Every human being is entitled to respect for their life and the integrity of their person. No one may be arbitrarily deprived of this right.

Guidelines on Policing Assemblies by Law Enforcement in Africa

- Use of Lethal Force: Prohibited unless strictly unavoidable to protect life, and only when all other means are insufficient. The assessment must be based on reasonable grounds, not on suspicions or presumptions.

- Restrictions on the Use of Firearms: Allowed only when there is an imminent risk of death or serious injury, or to prevent the commission of a grave crime threatening life. Requires identification and a clear warning before use.

- Firearms in Assemblies: Not appropriate for controlling assemblies, and must not be used to disperse a crowd. Indiscriminate discharge is a violation of the right to life.

General Comment No. 3 on the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights: The Right to Life (Article 4)

The intentional use of lethal force is prohibited unless strictly unavoidable to protect life and only when all other means are insufficient.

Europe

European Convention on Human Rights – Article 2

Right to life: Protected by law. Deprivation of life is not considered a violation when it is absolutely necessary to:

- Defend a person from unlawful violence

- Effect a lawful arrest or prevent escape

- Quell a riot or insurrection.

European Code of Police Ethics

All police operations must respect the right to life of all individuals.

Americas

American Convention on Human Rights – Article 4

Every person has the right to have their life respected, which is protected by law. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of their life.

Middle East and North Africa

Arab Charter on Human Rights – Article 5

Every human being has the inherent right to life, protected by law. No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of their life.

Implications on the Use of Force by Police

Discrimination and Use of Force

The illegal use of firearms is often linked to discriminatory practices. Police may systematically target certain groups, especially from marginalized communities, resulting in disproportionate use of lethal force.

- Police operations must be conducted without discrimination, and any use of force must be strictly necessary and proportionate to the imminent threat.

Planning and Protection of Bystanders

- Police must plan operations considering the lives of bystanders, suspects, and themselves. High-risk operations for civilians must be avoided, opting for times or locations with lower risks.

Restrictions on the Use of Firearms

- Automatic weapons are not appropriate for routine police activities. They should only be used in extreme circumstances and with clear instructions on when this is permissible.

Accountability and Justification

- Every use of firearms must be justified as necessary and proportionate. The use of force must be continuously assessed to avoid excesses.

Conclusion

The use of lethal force by law enforcement must be regulated by stringent standards to prevent discrimination and protect the right to life. Regional human rights standards provide essential guidelines that law enforcement must follow to ensure every intervention is legitimate, necessary, and proportionate.

Part 3: Defending Dignity and Our Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights: A Fundamental Pillar

Case of Amnesty International Activists in Turkey

In July 2017, ten human rights defenders, including Idil Eser, director of Amnesty International Turkey, were arrested during a workshop. Unjustly accused of “aiding a terrorist organization,” they were detained, released in October 2017, and four of them were sentenced in July 2020. After international protests, they were finally acquitted in 2023. According to Agnès Callamard, Secretary General of Amnesty International, this episode highlights politically motivated judicial proceedings aimed at silencing critical voices.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR)

Adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 10, 1948, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights establishes fundamental rights and freedoms for all human beings. It consists of 30 articles covering civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights, considered universal, inalienable, and indivisible.

Importance of the UDHR Today

Hugh Sandeman:

- The UDHR is revolutionary, establishing human rights for the first time in an international agreement.

- It reaffirms the universality of human rights, recognized by individuals and nations, despite attempts to deny or violate them.

Zainab Asunramu:

- It sets a standard for how every human being should be treated, regardless of gender, race, or age.

- Promotes a world of equality, respect, fair access to education and healthcare, and freedom of choice in marriage.

- Ensures equal rights for all, providing conditions of parity.

Regional Applications of Human Rights

Africa:

- African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights – Article 4: Protects the right to life and the integrity of the person.

- Guidelines on Policing Assemblies by Law Enforcement in Africa: Restrict the use of lethal force only when strictly necessary to protect life.

Europe:

- European Convention on Human Rights – Article 2: Protects the right to life, with the use of force only in strictly necessary circumstances.

- European Code of Police Ethics: Requires all police operations to respect the right to life.

Americas:

- American Convention on Human Rights – Article 4: Every person has the right to have their life respected, protected by law.

Middle East and North Africa:

- Arab Charter on Human Rights – Article 5: Protects the intrinsic right to life, prohibiting arbitrary deprivations of life.

Conclusion

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights remains a foundational document, ensuring rights and freedoms for all. Episodes such as the arrest of Amnesty International activists in Turkey underscore the importance of the UDHR in protecting critical voices and human rights defenders. Regional standards reinforce these rights, but it is crucial for all nations and law enforcement agencies to respect and implement these norms to ensure a just and equitable world.

Protection and Application of Human Rights Structure of Human Rights Protection

Human rights are guaranteed through a combination of legal enforcement at national and international levels, supported by global and regional bodies. At the national level, constitutions and laws enshrine human rights, while internationally, treaties and formal agreements negotiated between countries establish legal obligations for states. International organizations such as the United Nations, the Council of Europe, the Organization of American States, and the African Union are responsible for drafting, negotiating, and monitoring these treaties.

Universality of Human Rights

Human rights are universal and should be enjoyed by all, regardless of race, sex, creed, or religion. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is a historic document that sets out the fundamental rights and freedoms of all human beings, adopted by the United Nations General Assembly on December 10, 1948.

History and Context of the UDHR

1945: Establishment of the United Nations The Second World War highlighted the need to protect human rights globally. The horrors of the Holocaust, which resulted in the extermination of nearly 17 million people, spurred governments to establish the United Nations in 1945 to promote peace and prevent future conflicts.

1948: Adoption of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights In 1948, under the leadership of Eleanor Roosevelt, representatives from the UN’s 50 member states gathered to create a list of universal human rights. On December 10, 1948, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Key Rights Included in the UDHR

The Declaration includes 30 articles outlining civil, political, economic, social, and cultural rights. Some key rights include:

Article 1: Right to Equality

“All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights.” This article emphasizes the equality of all human beings.

Article 3: Right to Life, Liberty, and Personal Security

“Everyone has the right to life, liberty, and security of person.” This right is fundamental to the enjoyment of all other human rights.

Article 5: Freedom from Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment

“No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.” Freedom from torture is an absolute right.

Article 6: Right to Recognition as a Person before the Law

“Everyone has the right to recognition everywhere as a person before the law.” Being recognized as a person under the law is crucial for the exercise of human rights.

Article 12: Right to Privacy

“No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family, home or correspondence, nor to attacks upon his honor and reputation.” Privacy protects our dignity from unjustified interference by states or other powerful entities.

Article 28: Right to a Social and International Order

“Everyone is entitled to a social and international order in which the rights and freedoms set forth in this Declaration can be fully realized.” States have an obligation to create a society that preserves the dignity of all.

Article 30: Freedom from Interference in These Human Rights

“Nothing in this Declaration may be interpreted as implying for any State, group or person any right to engage in any activity or to perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms set forth herein.”

Conclusion

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights represents a milestone in the history of human rights, establishing a global framework for their protection and promotion. The historical events leading to its creation, such as the atrocities of World War II, underscored the importance of ensuring that human rights are universally respected. Through the UDHR and the ongoing work of international organizations, the rights and dignity of every human being are defended and promoted, reinforcing the need for constant commitment to human rights protection worldwide.

Human rights are closely interconnected. There is no hierarchy among human rights: each right holds equal importance and dignity. Respecting one right entails respecting others, while the violation of one right often leads to violations of others. For example, the right to freedom of expression is linked to the right to participate in government, and denial of freedom of expression can undermine political participation and vice versa.

Inalienability

Human rights are inherent to every individual and cannot be alienated. They cannot be bought, inherited, or transferred. No one has the right to deprive another individual of their rights, regardless of circumstances. This inalienability ensures that human rights are always present and applicable to all, protecting human dignity at all times.

Universality

Human rights are universal and apply to all human beings, regardless of nationality, place of residence, sex, national or ethnic origin, color, religion, language, or any other status. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights asserts that everyone is entitled to all human rights. States have the duty to promote and protect these rights for all without discrimination.

Kumi Naidoo’s Vision

Kumi Naidoo, former Secretary-General of Amnesty International, emphasized the need for a systemic view of human rights, recognizing that many contemporary issues are interconnected.

Here are some specific examples of interconnections between different rights:

Climate Crises and Human Rights: The climate crisis affects not only the environment but also inequality and social justice. Vulnerable communities are often the most affected by environmental disasters, leading to increased discrimination and economic inequality.

Gender Discrimination and Economic Exclusion: Gender discrimination is closely linked to economic exclusion. Women often face barriers in accessing education and employment, perpetuating cycles of poverty and violating their economic and social rights.

Civil and Political Rights and Economic Justice: People seeking economic justice often see their civil and political rights suppressed. The repression of peaceful demonstrations or social movements for economic justice represents a violation of rights to expression, association, and peaceful assembly.

Criticism and Controversies Regarding the Universality of Human Rights

While the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is widely respected, it is not immune to criticism. Some argue that human rights should be interpreted through a cultural lens, adapting the definition and application of rights to specific cultural contexts. This perspective questions the universality of human rights, suggesting that imposing universal values may undermine cultural diversity and impose Western norms on other societies.

Current Importance of the UDHR

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights remains relevant today for several reasons:

Universal Standard: The UDHR provides a clear standard for human rights that must be respected, protected, and fulfilled for everyone.

Integration into National Legislation: Many countries have incorporated UDHR principles into their laws and constitutions, providing a legal basis for human rights protection.

Guidance for Human Rights Advocacy Organizations: For organizations like Amnesty International, the UDHR serves as a source of inspiration and provides a common framework for activists worldwide to defend human rights.

Conclusion

Human rights are interconnected, indivisible, inalienable, and universal. The systemic view of human rights, promoted by leaders like Kumi Naidoo, helps us understand how various forms of injustice are linked and how protecting one human right supports and strengthens others. The UDHR remains a milestone in human rights advocacy, offering essential guidance to promote a world where every individual can live with dignity and freedom.

Case Study: Mother Mushroom and Human Rights

Case Context

Nguyễn Ngọc Như Quỳnh, known as Mẹ Nấm (Mother Mushroom), is a prominent Vietnamese blogger who was arrested in 2016 for peacefully expressing her opinions on Facebook. She was sentenced to 10 years in prison for “conducting propaganda against the State,” highlighting human rights violations in Vietnam, where over 100 activists and human rights defenders are detained for exercising their rights to freedom of expression, association, and peaceful assembly.

Specific Human Rights Violations

Freedom of Expression

Article 19: This article guarantees the right to freedom of opinion and expression, including freedom to seek, receive, and impart information and ideas of all kinds.

Freedom of Association and Peaceful Assembly

Article 20: Ensures the right to peaceful assembly and association.

Arbitrary Arrest

Article 9: Protects individuals from arbitrary arrest, detention, or exile.

Implications of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is crucial in ensuring that basic human rights are respected globally. The case of Nguyễn Ngọc Như Quỳnh demonstrates how the violation of these rights can have devastating effects on individuals’ lives and society at large. The UDHR covers various aspects of daily life and aims to protect the fundamental rights of every human being, ensuring their dignity and freedom.

Interconnection of Human Rights

Human rights are interconnected and indivisible. Nguyễn Ngọc Như Quỳnh’s rights violations are not isolated but part of a broader pattern of human rights repression in Vietnam. Violations of the right to freedom of expression often lead to violations of other rights, such as the right to freedom of association and peaceful assembly, underscoring the importance of considering human rights from a systemic perspective.

Importance of Human Rights in Daily Life

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights directly impacts our daily lives, ensuring the protection of our basic needs and essential rights:

Work and Equality

Articles 1, 2, 23: Guarantee equality, non-discrimination, and the right to fair and favorable working conditions.

Asylum and Refuge

Articles 13, 14, 25: Protect the right to freedom of movement, the right to seek asylum, and the right to an adequate standard of living.

Freedom of Expression and Family Life

Articles 2, 16, 19: Ensure non-discrimination, the right to family life, and freedom of expression.

Play and Children’s Health

Articles 16, 19, 24, 25: Promote the right to family life, freedom of expression, play and leisure, and the right to health.

Cultural Activities

Articles 19, 22, 24: Support the right to freedom of expression, social and cultural security, and leisure.

Conclusion

The case of Nguyễn Ngọc Như Quỳnh underscores the importance of human rights and the need for constant vigilance to ensure their respect. The UDHR remains a fundamental document for protecting universal human rights, offering a framework that helps individuals and organizations defend the rights and freedoms of all.

Why is education a human right?

Education is recognized as a fundamental human right for several essential reasons that deeply influence the individual and social development of every person. Here are some key points illustrating why education is considered a universal human right:

Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “Everyone has the right to education.” This article emphasizes that education is a fundamental right of every human being, without discrimination of any kind, such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, economic status, birth, or any other condition.

Reasons why education is a human right:

Individual Empowerment: Education provides people with the skills necessary to develop their potential and contribute positively to society. Without education, individuals are limited in their opportunities for personal and professional growth.

Promotion of Gender Equality: Equitable and universal access to education is essential to ensure gender equality. Girls and young women often face more significant barriers in accessing education compared to boys, perpetuating social and economic inequalities.

Poverty and Inequality Reduction: Quality education is a crucial catalyst for breaking the cycle of poverty. It provides individuals with the skills to access better economic opportunities and improve their quality of life.

Promotion of Peace and Tolerance: Education helps promote intercultural understanding, mutual respect, and tolerance. It enhances peaceful coexistence among individuals from different backgrounds, ethnicities, and socio-economic statuses.

Sustainable Development: Education is a critical element in achieving the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, particularly Goal 4, which aims to ensure inclusive, equitable, and quality education for all.

Examples of Human Rights Violations Related to Education:

Kuwait Case: Discriminatory policies in Kuwait deprive Bidun boys and girls of citizenship and thus access to free public schools, violating their right to education and non-discrimination.

Egypt: Restrictions imposed on political parties and Christian candidates during elections limit their right to political participation and, indirectly, their right to education through fair and non-discriminatory access to opportunities.

Czech Republic: The education of Romani children in “special schools” marks a form of discrimination based on ethnic origin, contravening the principle of equal access to education.

Latin America: Restrictions on updating legal documents for transgender individuals directly impact their access to basic public services, including education.

In summary, education is a fundamental human right that not only contributes to personal development and individual prosperity but also plays a crucial role in promoting peace, tolerance, and reducing global inequalities. Violations of this right, as illustrated in the examples above, highlight the ongoing need to protect and promote education as a universal and inalienable right of every individual.

If every individual truly had a voice and actively participated in the public affairs of their society, the world could become significantly different and more just. Here are some reflections on how such an inclusive and rights-respecting society might look:

Freedom of Expression and Independent Media

A rights-respecting society would ensure freedom of expression for all, without fear of repression or censorship. Media would be independent and free to report news objectively, without being influenced by political or economic interests. This would enable a continuous flow of information and well-informed public debate.

Active Participation in Decision-Making

Every member of society would have the opportunity to actively participate in decision-making processes. This could include voting for political representatives, participating in public consultations on community issues, and having a say in decisions concerning public policies, urban development, environmental issues, and much more.

Justice and Equality

Courts would be independent and impartial, ensuring that every individual has access to a fair trial and effective remedy in case of rights violations. This would promote trust in the legal system and contribute to reducing inequalities and discriminations often resulting from a compromised judicial system.

Inclusive Society Respecting Diversity

Such a structured society would welcome and respect diversity of opinions, cultural backgrounds, ethnicities, religions, and sexual orientations. This inclusivity would foster mutual understanding, tolerance, and peaceful coexistence among diverse groups within society.

Positive Impact on Social and Economic Well-being

With broader democratic participation and greater social justice, decisions made would be more representative and better respond to people’s real needs. This could lead to more effective policies to address poverty, improve access to education and healthcare, and promote sustainable economic development.

Conclusion

Imagining a society where every individual has real decision-making power and actively participates in the democratic process suggests an environment where injustices are reduced, human rights are respected, and collective well-being is a priority. Achieving this ideal requires collective commitment to strengthen democratic institutions, protect fundamental rights, and promote a culture of civic participation and public accountability.

Part 4 HOW TO TAKE ACTION

Often, the human rights movement has focused on exposing human rights violations, calling out and shaming governments and corporations that violate human rights as a way to ensure accountability and prevent further violations in the future.

In an era of rampant misinformation, telling people they are wrong can actually reinforce their opinions if it conflicts with their values and beliefs. So, how can we communicate human rights more effectively?

Plant Hope, Not Fear

Years of research show that human rights communication must also focus on hope and opportunity, not just fear and threats.

Positive Statements

Example: “You care about human rights and want to find solutions to human rights violations.”

To solve any problem, it is necessary to focus on solutions, not just on the problems. This is also true when dealing with human rights abuses. While it is essential to expose violations, we must also show how to resolve them. Positive communication means focusing on what we truly want, not just condemning others.

Building on Existing Commitments

Example: “Because you care about your family, you also care about human rights.”

Everyone has commitments in life and is likely to take actions that support them. For some, their biggest commitment might be protecting their family or improving their reputation among peers. Finding ways to connect those commitments to human rights can be an effective way to gather support.

Social Norming

Example: “People in your community are taking action for human rights.”

We are all influenced by social norms—the rules that define what is considered normal behavior for people like us. This happens both consciously and unconsciously. To expand support for human rights, it can be helpful to show that MANY people, including those similar to the person you are speaking to, are standing up for human rights in their community. Everyone can be a human rights defender.

What other strategies come to mind that have proven effective in communicating human rights in your context?

In 2012, a silent march interrupted a peaceful summer morning on the beautiful Rabbit Island in Lampedusa, southern Italy, where thousands of migrants arrive every week. The core of the campaign was the pact between Italy and Libya, eventually agreed upon in February 2017, which authorized authorities to return migrants to a country where humanitarian agencies report they face torture and abuse.

In 2023, eleven years after this campaign, the situation for migrants and asylum seekers has not improved and has led to the deaths of many, including women and children, as well as violations of the rights outlined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Amnesty International has urged the European Union to stop assisting in returning people to the hellish conditions in Libya.

Let’s explore some ideas on how to communicate human rights more effectively to others.

STEP 1 – Identify a Problem

Learn more about the issue and how people in your community feel about it. Read newspapers, magazines, books, reports, and social media on the subject, or contact relevant officials for information.

STEP 2 – Choose Your Action

After analyzing the local context, brainstorm ways to reach as many people as possible.

Think of various ideas, even if they seem unusual. Then, choose one or two approaches that seem the most feasible and are likely to make a difference.

Here are some examples for inspiration:

Raise Awareness – Use social media platforms to spread awareness about a human rights issue. Choose a catchy, simple, and meaningful slogan to reach as many people as possible.

Amplify Voices – Interview people affected by the issue you’ve chosen and, with their consent, publish the results.

Influence Opinions – Write a letter to the press, an article for a magazine, or a blog post to shape opinions and reach a wider audience.

Evoke Empathy – Write a poem, design a mural, compose a song, or paint a picture. Art can be a powerful way to tell stories and evoke empathy.

Speak Up – Use your voice and speak out when you witness racism or hate speech in your daily life. Your courage could inspire others to follow your example.

Disrupt Routines – Take action in the streets or other public spaces! Try “Guerrilla Theatre” with spontaneous and unexpected performances or organize a flash mob to reclaim public space. Check out examples from different countries.

STEP 3 – Create a Positive Message

We shouldn’t just expose abuses—we should also offer hope to people.

This can be challenging for those determined to prevent the worst abuses from happening again and who believe that injustice must be exposed and shared with the world. However, we must show that we can improve things together.

We have explored how to speak in favor of human rights values and actions; now, we will begin thinking about initiatives and activities you can use. Above, you can see the “Write for Rights” campaign, Amnesty’s annual global initiative that encourages people worldwide to take action by using the power of letter writing to draw attention to cases of injustice.

Too often, human rights are treated as if they exist only on paper. That is why we must stand up and claim our rights.

But how can we do this?

IDENTIFY THE PROBLEM

Start by identifying the issues affecting equality in your community. What is wrong, and what needs to change? Which human rights are involved? Are there any rights being denied? Use your assessment as a reference. For example:

- People are not allowed to wear religious accessories in public.

- Those living in slums lack access to clean water.

- Transgender students are forced to wear gendered uniforms and use bathrooms that do not align with their identity.

- Lack of access to public transport and/or spaces for people with disabilities.

- Police discrimination against young people of a certain skin color.

- Girls drop out of school due to a lack of tuition fees, while their brothers remain in school.

If in doubt, use the Universal Declaration of Human Rights as a reference.

Here are some examples to help you identify issues affecting your community:

- Watching the news

- Following cases on social media

- Reading newspapers and magazines

- Talking to community members

- Collaborating with a human rights organization

Reflect on the following questions:

- WHAT is the issue you identified?

- WHAT is wrong, and what needs to change?

- WHY does this issue occur?

- WHO is affected?

Choose allies in your community